Cupola Geckos Rediscovered! (A New Pet Gecko? Probably Not)

Have you ever heard of Cupola Basin geckos? If not, don’t worry! It’s actually even rarer to find people who are familiar with this species. And now that you’ve heard of it, you must be eager to learn more about this gorgeous but evasive little reptile!

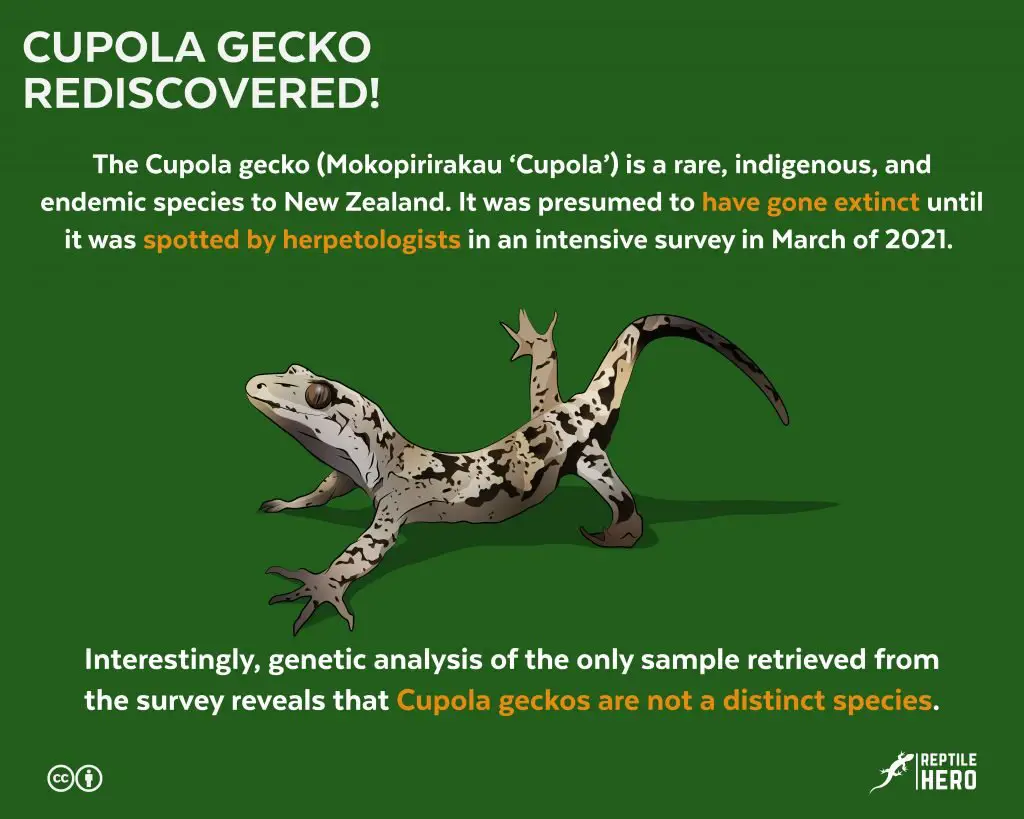

The Cupola gecko (Mokopirirakau ‘Cupola’) is a rare, indigenous, and endemic species to New Zealand. It was presumed to have gone extinct until it was spotted by herpetologists in an intensive survey in March of 2021. Interestingly, genetic analysis of the only sample retrieved from the survey reveals that Cupola geckos are not a distinct species.

So if Cupola Basin geckos are not a unique species as experts initially thought, what are they? Find out the truth of the matter by reading on!

Reappearance of Cupola Geckos: New Sightings

Overall, there are only 3 confirmed sightings of the beautiful and rare Cupola gecko. With each sighting made years—even decades—apart. As such, much about them remains a mystery.

However, scientists are not giving up. In fact, they are quite eager to learn more about these amazing creatures and share more of their discoveries with us!

2021 Sighting of 4 Live Cupola Gecko Specimens

In the early months of 2021, a team of herpetologists conducted a targeted survey in the Nelson Lakes National Park for the Cupola Basin gecko. Four specimens were found quite a significant distance from each other. The team was also able to collect a tail specimen for DNA analysis.

Sightings of multiple Cupola geckos are definitely a welcome surprise, especially if we are to consider how many previous efforts had already failed to catch a glimpse of even a single specimen.

Because of the rarity of their sightings, some have even resigned themselves to the possibility that Cupola geckos might have already gone extinct. So imagine their surprise when the Cupola Basin gecko—also dubbed the Cupola “ghost”—finally graced us with its presence once again!

What happened during the March 2021 expedition in Nelson Lakes National Park?

The team of herpetologists, headed by Ben Barr, flipped over a couple of thousands of rocks for several days, to the point where they almost lost their fingerprints.

During the first few days of the March 2021 expedition, the team only found shed skin and droppings. However, this did nothing but boost the team’s morale as these findings serve as evidence that they may be near their target [1].

Eventually, they did come across the ever-elusive Cupola gecko.

- The first specimen was a juvenile female Cupola gecko that was found high up the mountains.

- It then took them approximately 1.24 miles (2 km) before finding the second wild specimen—an adult male Cupola gecko.

- On their third sighting, the scientists came across a gravid female that was basking under the evening sun.

- Then, on the last day of their survey, they saw their fourth and final Cupola gecko.

Before letting the first three geckos go about their day, the herpetologists measured and photographed them.

Unfortunately, upon flipping the rock the fourth gecko was hiding under, the gecko got spooked and darted away—but not without leaving its tail behind. So you could say that having that last gecko give them the slip was actually a blessing in disguise.

When and Where was the Cupola Gecko First Discovered?

The Cupola gecko was first discovered scurrying up the scree slope, above the treeline, near the Cupola Basin in Nelson Lakes National Park way back in 1968. It was a juvenile specimen with a striking pattern compared to other known geckos in the Mokopirirakau genus. Hence, it was thought to be a new and yet-to-be classified distinct species.

John Pearson, who was originally doing his research on red deer, only came across the juvenile Cupola gecko by pure coincidence. He made the discovery while he was on his way back to the New Zealand Forest Service Hut.

After picking the juvenile Cupola gecko up and placing it inside his woolen shirt’s pocket, Pearson brought it back to the hut with him. He placed it inside a glass preserving jar that had holes on the lid for ventilation. To feed his new roommate, he would catch flies.

Once he left Nelson Lakes, he brought the gecko with him—with a plan to give the specimen to a lizard expert for assessment. Pearson kept the gecko with him until it died. Sadly, not much else was discovered about the rare species other than its physical appearance.

Have There Been Other Sightings of the Cupola Gecko?

The only other confirmed sighting of Cupola geckos after the 1968 discovery—but before the more recent sighting of 2021—dates back to 2007. All three were documented with photographs.

In 2007, the second confirmed sighting of Cupola geckos was by Roger Wadell together with Rowan Grey. This rediscovery was made while they were trekking through the Sabine Valley. They found the little guy basking out in the open, directly under the sun.

Fun Fact: The photographs Wadell and his son took of the Cupola gecko they found were used in posters, distributed around Nelson Lakes, that urged park visitors and trekkers to report possible sightings.

Below are some of the unconfirmed sightings:

- 10 years later (in 2017), Matthew Shields, a tramper, wrote about spotting a gray gecko around the Travers Saddle. He even created a rough sketch of the gecko, which looks highly similar to Cupola geckos.

- Before the rediscovery in March 2021, a volunteer working with the Department of Conservation found another gecko that looked like a Cupola gecko after turning over a rock in January.

Other than the aforementioned confirmed and unconfirmed sightings, several other targeted and extensive surveys have been done in the Nelson Lakes National Park throughout the years (e.g., 2006 and 2019). Unfortunately, these trips failed to locate even a single Cupola gecko.

What Do Cupola Geckos Look Like?

Unlike other geckos grouped under the Mokopirirakau genus, the adult Cupola gecko predominantly has gray coloration, as well as black V or W-shaped markings on its back. Cupola geckos also had distinct markings on their heads: 1) a V between their eyes and 2) T from their eyes to their nose.

The Cupola Basin gecko looked highly similar to most other forest geckos in New Zealand. However, they did have unique morphological features that set them apart from the other geckos in the Nelson Lakes area—and the rest of the country for that matter [2, 3].

Other known physical traits of adult Cupola geckos include:

- Eyes: Gray-brown or gray-olive iris with fine black lace-like patterns

- Mouth: Bright orange mouth lining

- Snout: Relatively shorter snout

- Head: Considerably more triangular head shape

- Abdomen: Mainly gray with some black speckling

- Side of the Body—Gray coloration on the sides with bands or patches

- Pads/Soles—Light yellow or cream pads and/or soles

- Tail—Original or intact tail is more or less longer than its entire body length

Interestingly, juvenile Cupola geckos have a darker brownish-gray coloration with gray chevron-like markings on their back and dark yellow speckling. Their abdomens also have some speckling.

Do Cupola geckos have any lamellae?

It is still uncertain whether Cupola geckos possess sticky toe pads due to the presence of lamellae. However, other Mokopirirakau geckos have been confirmed to have up to 14 lamellae in their markedly slender toes.

Learn more about lamellae and sticky toe pads in our article explaining how geckos walk on walls.

Why Were They Named Cupola Geckos?

Cupola geckos were named after their suspected close relatives and home. The origins of the common name of Cupola Basin geckos—even their tag name or placeholder scientific name of Mokopirirakau ‘Cupola’—has very simple origins.

Simply put, Cupola Basin—or more just Cupola—part of their name is a nod to the area where it was first discovered and to its suspected primary habitat.

The word Mokopirirakau comes from the te reo Māori term “moko-piri-ākau” which means “lizards that cling to trees.” This has been used to refer to most forest geckos in New Zealand. Hence, the name is assigned to the genus.

Other geckos in the Mokopirirakau genus include:

- Black-eyed gecko (Mokopirirakau kahutarae)

- Cascade gecko (Mokopirirakau ‘Cascades’)

- Cloudy gecko (Mokopirirakau nebulosus)

- Forest gecko (Mokopirirakau granulatus)

- Okarito or broad-cheeked gecko (Mokopirirakau ‘Okarito’)

- Open Bay Islands or moko taumaka gecko (Mokopirirakau ‘Open Bay Islands’)

- Otago black-eyed, Southern black-eyed, or Hura te ao gecko (Mokopirirakau galaxias)

- Roys Peak or orange-spotted gecko (Mokopirirakau ‘Roys Peak’)

- Southern forest, tautuku or blue-eyed gecko (Mokopirirakau ‘Southern Forest’)

- Southern North Island forest or ngahere gecko (Mokopirirakau ‘Southern North Island’)

- Tākitimu or takatimus gecko (Mokopirirakau cryptozoicus)

All geckos in this genus are largely hard to come by—save for forest geckos that have been raised and bred in captivity as part of conservation efforts.

Important Note: However, you must keep in mind that what we recognize as their scientific name is not yet an official designation. With the new revelations we have yet to obtain from the genetic analysis done on the sample, this will likely be changed and updated accordingly.

The Scientific Classification of Cupola Geckos

The tag name of the Cupola gecko has not always been Mokopirirakau ‘Cupola’. Rather, the placeholder for its scientific name has been revised several times already.

Past tag names for Cupola Basin geckos are:

- Hoplodactylus ‘Cupola’ in 2007

- Hoplodactylus aff. granulatus ‘Cupola’ in 2010

The tag name was then changed from Hoplodactylus to Mokopirirakau “Cupola” in 2013. Mainly, the change was because Hoplodactylus geckos are generally much larger and they sport a brown-gray coloration.

Note: When you see “aff.” in scientific names, it is the abbreviation of affinis which means that it has an affinity with another species. In this case, Cupola geckos have been pointed out to have some affinity with forest geckos (Mokopirirakau granulatus).

What Family Does the Cupola Gecko Belong To?

Even though much of the Cupola geckos remains unknown, some things have been determined with relative certainty—of experts on New Zealand lizards like geckos and skinks. One thing is already for certain.

Cupola geckos belong to the Diplodactylidae family of reptiles—or more specifically, geckos. This means that it is in the same family as:

- Auckland green gecko (Naultinus elegans)

- Beaded gecko (Lucasium damaeum)

- Clawless gecko (Crenadactylus ocellatus)

- Crested gecko (Correlophus ciliatus)

- Marbled gecko (Oedodera marmorata)

- New Caledonian giant gecko (Rhacodactylus leachianus)

- Robust velvet gecko (Nebulifera robusta)

- Vieillardi’s chameleon gecko (Eurydactylodes vieillardi)

- Western spiny-tailed gecko (Strophurus strophurus)

This family of geckos includes more than 150 distinct species spread over 25 genera, and they can be found in New Zealand, Australia, and New Caledonia

On average, Diplodactylidae geckos are well-researched and assessed. Unfortunately, this is not true for most if not all Mokopirirakau geckos, including the Cupola gecko.

What Does the Natural Habitat of Cupola Geckos Look Like?

Unfortunately, the refuge sites of Cupola geckos are yet to be uncovered. Nevertheless, experts believe that their population can only be largely found in the Nelson Lakes National Park in the southern island of New Zealand.

To be more specific, Cupola gecko sightings have mostly been made in the Cupola Basin and Sabine Valley of Nelson Lakes. In other words, they are principally found in alpine areas—unlike most other species which live in much warmer regions.

Distribution of Mokopirirakau Geckos in New Zealand

Cupola geckos were formerly recognized to be geographically isolated from other species. But more recent data shows that their speculated population distribution closely coincides with that of forest and black-eyed geckos.

Scientists theorize that Cupola geckos may utilize the following as habitats:

- Beech forests

- Boulder fields

- River flats and grasses

- Scree slopes

- Shrublands

- Sub-alpine scrubs

However, park visitors and herpetologists have only ever spotted Cupola geckos while they are hiding under rocks or basking openly in the sun. It is uncertain whether or not they live in loose colonies for more permanent refuge sites just like leopard geckos. We still have a lot to learn about these rarely seen geckos.

Is the Cupola Gecko a Distinct Species?

The rediscovery of Cupola geckos brought with it more questions and possible answers to both new and old questions thanks to the tail sample obtained from the 2021 targeted survey.

So, are they the same? Quite surprisingly, the answer is yes.

The results of the DNA analysis done with the tail left behind by one of the Cupola geckos, found during the 2021 expedition, indicate that Cupola geckos (Mokopirirakau ‘Cupola’) are indistinct from forest geckos (Mokopirirakau granulatus).

Rather than being a unique species—as was initially thought by scientists—they are actually just forest geckos with a distinct morphology (colloquially called morph). In fact, if we are to compare available descriptions for both, you will realize that Cupola geckos do indeed closely resemble forest geckos.

Learn more about the science of morphology, as a whole, in our article on leopard gecko morphs.

Furthermore, if we were to look at their distribution, side by side, it makes a lot of sense. Cupola geckos most likely separated from the larger population

Can You Keep Cupola Geckos as Pets in Captivity?

Cupola geckos, like every other New Zealand lizard, can neither be bought, sold, or caught regardless of whether you are in the country or not. This means that keeping Cupola geckos in captivity as pets is generally illegal. The exemption to that rule is if you have a Wildlife Act authorization from the Department of Conservation.

Still, getting the permit to keep Cupola geckos is easier said than done—especially if you have little to no experience in keeping New Zealand lizards according to proper husbandry standards.

Not to mention, it’s still unclear if you would need a First Level permit since Cupolas are indistinct from forest geckos, or a Higher Level permit because it’s a very rare species that only has confirmed sightings for 6 specimens.

Additionally, much of their optimal husbandry and dietary needs are yet to be determined by herpetologists.

So although the rediscovery of Cupola geckos has brought much excitement within the reptile community, keeping them as part of our reptile collection or family is not advisable.

Nonetheless, you can learn more about how to keep Cupola geckos, and other New Zealand wildlife, in captivity on the official website of the Department of Conservation.

Then, what does the rediscovery of Cupola geckos mean for regular and professional keepers and breeders?

The rediscovery of Cupola geckos, and many other rare and threatened reptiles, call us reptile owners to be more responsible as a whole. More importantly, it encourages us to work with local wildlife organizations and engage in conservation efforts so that these majestic scaly animals don’t go extinct.

Moreover, the discovery of such cryptic and unique species only widens and improves our knowledge of reptiles as a whole. It helps us better understand their behaviors and needs.

For example, the fact that alpine geckos can live actively in environments with ambient temperatures that drop can as low as approximately 33ºF (1ºC) sounds impossible but it is. Meaning, there might be something else more to thermoregulation in reptiles than what we are currently aware of.

Further Questions

On average, how big can Cupola geckos get?

The average snout-to-vent length (SVL) of adult Cupola geckos is estimated to be around 3 in (80 mm). Their average weight remains undetermined, but it is likely to be more or less half an ounce or 15 grams.

Are Cupola geckos solitary or communal species?

Because the refuge sites or Cupola geckos have not yet been found, scientists cannot say for certain if they are solitary or communal by nature. However, if they are anything like the other Mokopirirakau species, then they are more likely to be solitary creatures.

How long can Cupola geckos live?

Though the average lifespan of Cupola geckos is unknown, scientists think that it may be around 20 to 30 years. But the record for forest geckos shows that they can live for up to 40 years. It’s also worth noting that New Zealand geckos and skinks are some of the longest living lizard species on earth.

What is the conservation status of Cupola Geckos?

The conservation status of Cupola geckos is presumed to be threatened considering how rare their sighting is and the status of other closely-related geckos. However, it is still difficult to know for sure since they are largely considered as a Data Deficient species. Furthermore, Cupola geckos have been listed under the Reappearing IUCN red list.

Why are Cupola gecko sightings so rare?

Many factors have likely contributed to the rare sightings of Cupola geckos including 1) significant presence of predators, 2) undetermined habitat preference, and 3) uncertain life or natural history.

Are Cupola geckos diurnal, nocturnal, crepuscular, or cathemeral?

Due to the lack of significant data from extensive observation, scientists cannot say for certain if Cupola geckos are nocturnal (active at night) or cathemeral (active during the day and/or night). However, sightings of wild Cupola Basin gecko specimens basking in the sun may be evidence that they are indeed cathemeral.

Do Cupola geckos give birth to live young or lay eggs?

Because all diplodactylid geckos in New Zealand are known to exhibit viviparous, experienced herpetologists believe that Cupola Basin geckos give birth to live young rather than lay eggs. It is also theorized that they can give birth to two babies for each pregnancy—typically in the summer.

Are Cupola geckos a terrestrial or arboreal species?

Cupola geckos are thought to be terrestrial species, in large part since they are mostly found on the ground and under rocks. Thus, they are also recognized to be saxicolous—they may live among the rocks. But there is a possibility that they may also be partly arboreal, being genetically indistinct from forest geckos.

What do Cupola geckos eat as part of their natural diet?

Scientists think that similar to other geckos in the area, they are omnivorous geckos. As such, numerous insects and plants native to the Nelson Lakes National Park are likely to be part of a Cupola gecko’s normal diet. Cupola geckos may eat beetles, moths, spiders, native flowers, small berries, and even pollen or nectar.

Do Cupola geckos produce vocalizations?

Like other Mokopirirakau geckos, one can expect Cupola geckos to produce vocalizations in a variety of situations. For instance, they may produce chirp-like sounds or simply squeal when they are stressed.

Summary of Cupola Geckos Rediscovered

Contrary to the initial theory of herpetologists in New Zealand, the Cupola geckos are not a new and distinct species of geckos. However, very little information is available to definitively show whether they have other significant differences, excluding morphological features.

Reptile keepers and breeders in the USA cannot keep Cupola geckos unless they can move to New Zealand and become residents or citizens there. Moreover, since it is considered very rare and possibly threatened, there is less chance that one would be easily granted a Wildlife Act authorization permit.

Sources

[1] https://www.pressreader.com/new-zealand/nelson-mail/20210410/281526523868424

[2] https://www.reptiles.org.nz/

[3] https://books.google.com/books/about/Reptiles_and_Amphibians_of_New_Zealand.html?id=CypnxQEACAAJ

![Why Is My Gecko’s Poop Black and White? [With Science]](https://www.reptilehero.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/gecko-poop-black-white-cc-768x614.jpg)

![Do Leopard Geckos Need Heat Mats? [Myth or Truth]](https://www.reptilehero.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/does-gecko-needs-heat-mats-cc-768x614.jpg)